Record debt just keeps getting higher

There’s a narrative on Wall Street that just won’t go away. It tells us that US government borrowing and spending has spiraled too far out of control. And when the bills come due, we won’t be able to pay them.

And eventually, the chickens are gonna to come home to roost. This debt “bubble” is going to blow up in our face and take down the economy (and stock market).

I want to address this today because knowledge around these issues builds more confidence and conviction. And these things help us become more disciplined investors. Which tends to lead to better long-term investment results.

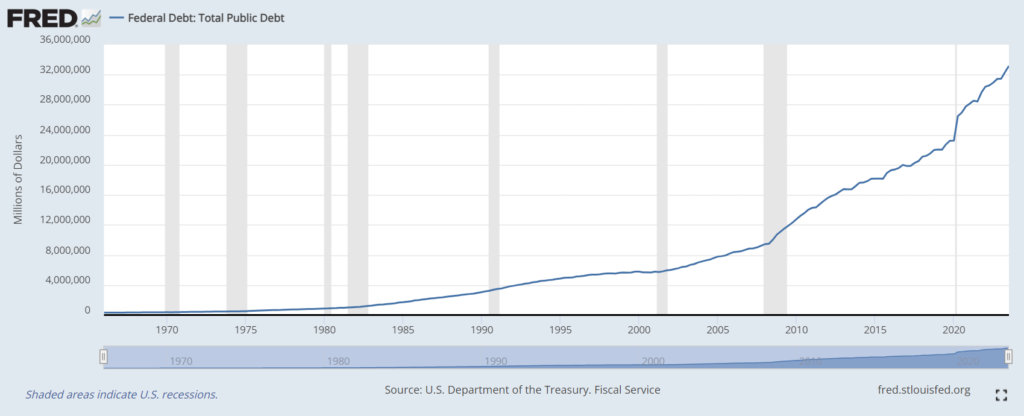

It’s true that debt has hit incredibly high levels. There’s no denying that. Here’s a chart that illustrates this:

The total amount of federal debt in the United States has now reached a whopping $34 Trillion. Sometimes, it can be hard to appreciate how big this number actually is, so let’s write it out in long-form: $34,000,000,000,000.

And it doesn’t show any sign of slowing down. As you can see here, it just keeps ballooning. Day in. Day out.

BUT…servicing the debt is what really matters

As I’ve mentioned before, it’s not the size of the debt that matters. It’s the ability to service the debt.

In other words, can the government make the interest payments?

It’s important to understand that government debt is very different than the debt you or I would take on.

When we borrow money, we’re the buyer. We borrow so we can buy some good or service.

When the government borrows money, they’re actually the seller. They’re selling treasury bonds to an investor (lender).

This is important because — unlike us — the US government has a vast and deep pool of buyers around the world that demand US Treasury securities.

This is because they are largely considered a “risk-free” asset. Which is why they exist in nearly every institutional investment portfolio — from governments and pension funds to insurance companies and mutual funds.

You and I don’t have this luxury.

So, whenever these loans come due, there’s always an ample amount of new and repeat buyers. Oftentimes, the buyers just roll over into a new agreement.

If the US ever ceased to be the world’s leading economy and the dollar ceased to be the world’s reserve currency, this could change.

But until then, the question we need to answer is: can the US government afford its interest payments?

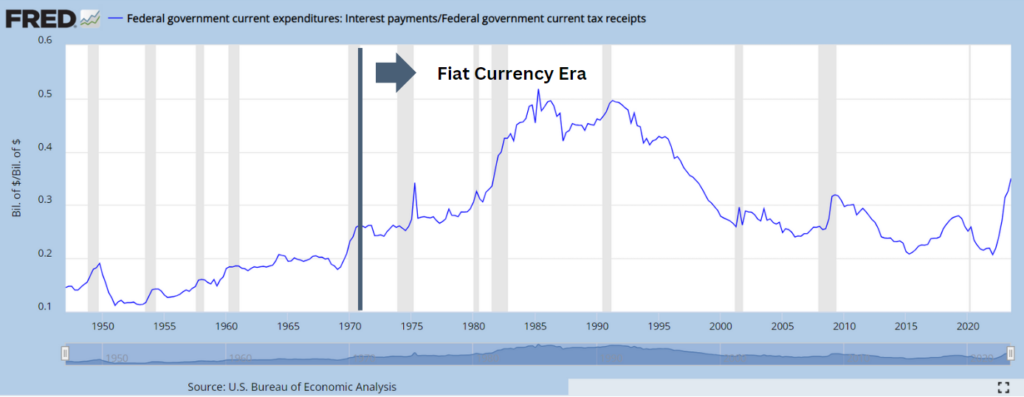

The following chart shows the government’s interest payments relative to the amount of tax revenue they collect. Despite the recent spike, interest payments are still only around 35% of total revenue.

Think of it this way: if you owed $35 and earned $100, you could pay off your debt and still have $65 left to spend on anything else. Currently, the US government is able to spend about 65% of their tax revenue on things other than interest payments.

As the chart illustrates, a 35% ratio isn’t that high in the modern era.

As a reminder, before 1971, each dollar was backed by physical gold. Since then, each dollar is backed by nothing but the full faith and credit of the US government.

This is important because in the fiat era, the government can simply print more money if they need to. Because of this, you would expect borrowing to be higher than it was during the gold-standard era.

So, as of today, it looks like the government should have no problem servicing the debt.

What if the debt service ratio keeps going higher? Will that be bad?

The common view is yes, if the debt service ratio moves higher, it would be a bad thing for the economy (and ultimately the stock market).

However, it’s really important to challenge common views.

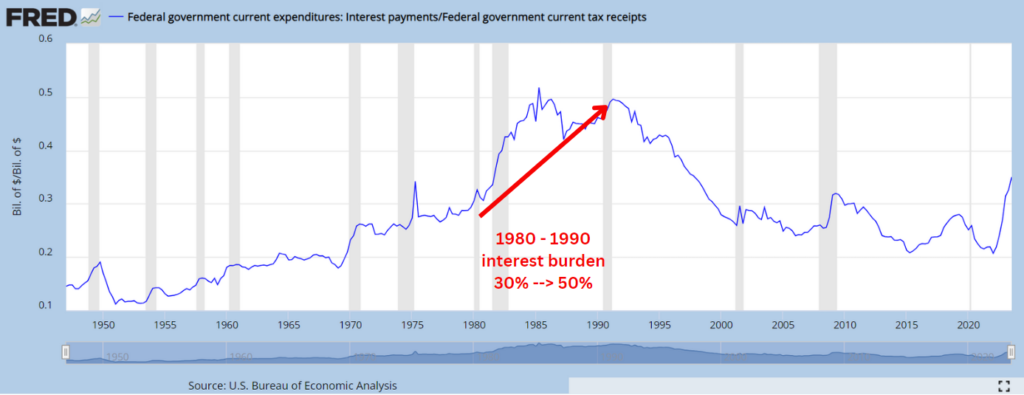

Let’s take a look at the last time the debt service ratio moved significantly higher, the way it has recently. This took place in the early 1980’s and the upward trend didn’t sustainably reverse until we reached the 1990’s.

As you can see below, in 1980, the government spent approximately 30% of its tax revenues on interest payments. And over the course of that decade, this number moved all the way up to 50%.

Counterintuitively, this was not bad for the economy or stock market. On the contrary, it was the beginning of a secular boom for both.

From 1980 – 1989, GDP (the primary indicator of economic growth) grew by an average of +3.1% per year. And the S&P 500 delivered an annualized return of +17.01%, including dividends.

Considering the historical annual return for stocks is around +10%, this was an excellent decade.

What if the government’s debt service ratio goes down? Would that be good?

Once again, here, the common view is yes.

This is why you always hear people clamoring for a balanced budget. Everyone views too much debt to be a drag on growth and an overall bad thing for the economy.

But the data paint a much different picture.

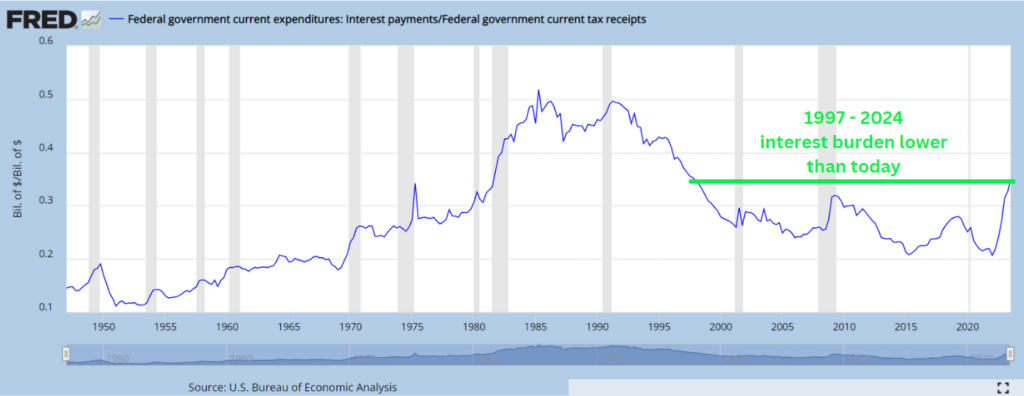

As you can see below, the government currently has the highest debt burden since 1997. Oddly enough, this was the year that President Clinton signed the Balanced Budget Act — which was widely applauded as a great thing for the economy.

Unfortunately, what followed was anything but great.

We had the two worst stock market crashes since the Great Depression. The first one being the dot-com bubble popping in 2000 and the second one being the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009.

From 1997 – 2022, GDP growth only averaged +2.29% annually. And the S&P 500 only delivered an annualized return of +8.89% including dividends (well below the +3.1% and +17.01% during the high and rising debt-burden scenario above).

When used properly, debt fuels economic growth

As the scenarios above illustrate, debt is not a bad thing. It’s just a tool.

Sort of like a hammer. Could a hammer be used as a weapon to hurt or kill someone? Yes. But it can also be used to build amazing stuff.

Likewise, debt can be used poorly. But it can also be put to good use and create a lot of value. And when this happens, it can be like rocket fuel to economic growth.

If anything, a higher debt burden can act as somewhat of a regulator against excess government spending. For example, if they’re spending half their tax revenues on interest payments, there’s a lot less to go around and support other important government functions.

This provides incentive to borrow and spend in a more efficient way.

On the other hand, when interest rates are near 0% — like they were for much of the past 15 years — money starts to become worthless. Which can result in really inefficient borrowing and spending.

Right now, the Fed’s projections are showing a reduction of interest rates over the next three years. With projections showing the current “effective fed funds rate” of 5.33% falling down into the 2-3% range.

In my opinion, this would be ideal. It would relieve some of the government’s debt burden, while also remaining high enough for money to be valued and used in an efficient way.

But whatever the case ends up being, I do not think government debt is a reason to be worried about the economy or the stock market at the moment.