Howdy friend! This week’s newsletter is brought to you by a fellow subscriber. He emailed me during the week and asked if I thought we could be headed for another “lost decade” scenario. So today, I’ll share my take on this. And if anyone else has questions, please let me know! Your questions are a great way for me to create the most beneficial content for you.

By “lost decade,” I mean a long period of time where the stock market has a lot of ups and downs, but actually goes nowhere. The classic example of this is the period of “stagflation” in the 1970’s. Stagflation is a combination of slowing economic growth, high unemployment and high inflation.

In November 1968, the S&P 500 reached a level of 109. And during the week of August 9, 1982, it reached a low of 102. From that point forward, the stock market would climb and never return anywhere close to these levels again. But nearly 14 years without any progress is tough. Granted, patient investors received dividends. But that doesn’t make up for all that lost time.

Thankfully, I don’t think we have to worry about anything like this happening today. Looking out over the next decade, I expect pretty normal stock market returns – maybe even better than normal, given the bear market we are currently in.

The Role of Innovation

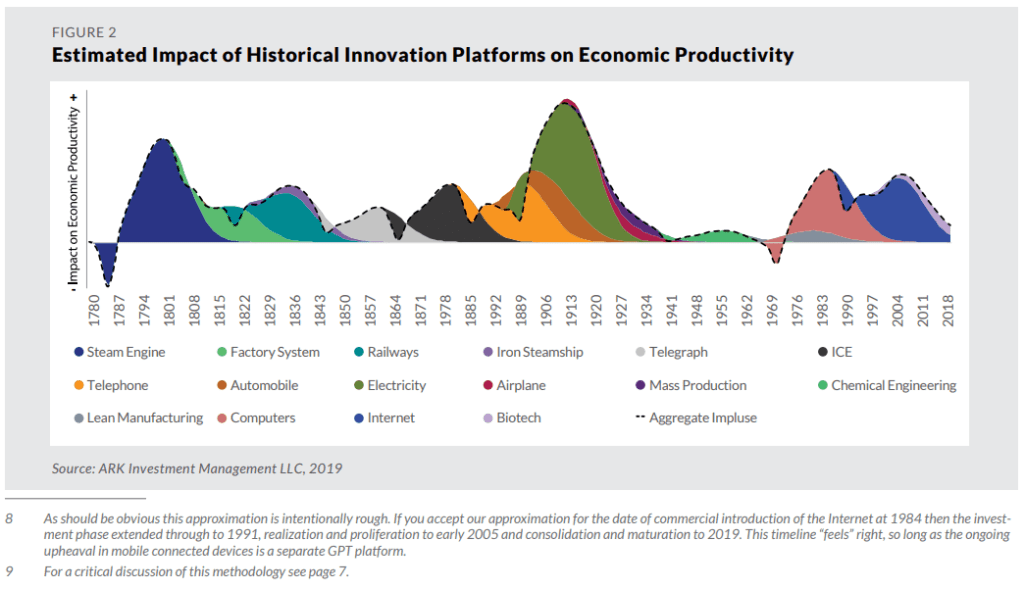

The 1970’s period of stagflation seems to have been caused by a lack of innovation in the decades preceding it. This chart is from a research article by an investment manager I respect.

To summarize the article – innovation increases productivity (economic growth) and reduces costs (deflation). This is the polar opposite of stagflation. Prior to the 70’s, we saw nearly four decades of little to no innovation. But today, innovation is everywhere – from artificial intelligence to blockchain technology to gene editing.

Now granted, we need to take this with a grain of salt. It comes from a company whose objective is to sell disruptive innovation funds. But their perspective is very logical, in my opinion. When you’re going through a depression and a huge global war, the priority is surviving – not thriving. Innovation takes a back seat to creating jobs and winning a war.

And after winning the war, economic prosperity for the US and its allies reached a high level. Things were probably a little too good for innovation to thrive. I think there’s a sweet spot between “the good life” and “survival,” where innovation thrives. And we spent several decades pretty far removed from that spot.

Recent History

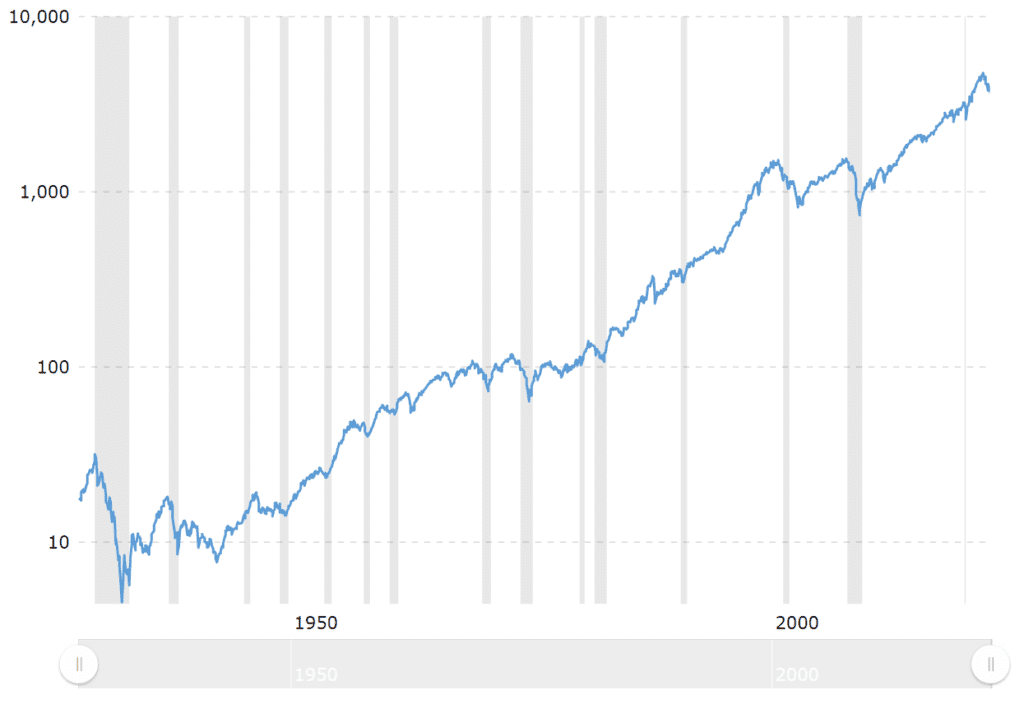

We also have to remember that we are coming out of a “lost decade” in the 2000’s. When looked at from this perspective, the current environment doesn’t look overly excessive. Certainly nowhere near the levels of excess from the late 90’s – which resulted in the dot com bubble and worst stock market crash since the Great Depression.

Here is a logarithmic chart of the S&P 500, from MacroTrends. As you can see, given the context of what we were coming out of, the recent stock market rise looks pretty normal.

Generational Tailwinds

Even from a generational perspective, the future looks promising. We are transitioning from the Boomer economy to the Millennial economy. Soon, millennials will outnumber all other generations in positions of influence. And this should only accelerate the adoption of new technologies and innovations that will drive the economy forward.

From the early 1980’s until the dot com peak in 2000, the stock market went through almost 20 years of great returns. Driven by a massive boomer population that received a major boost from technology – mainly computers and the internet. Now we have a massive millennial population that is receiving perhaps an even greater boost from technology. This should be a powerful tailwind for the economy for a long time.

_________________________

Have questions or want to learn more? Schedule a Video Chat

If you’re new to RW Weekly, here is my disclaimer: Nobody can predict short-term stock market movements on a consistent basis, over multiple market cycles. Not even the most skilled investment managers, who spend most of their waking hours dedicated to trying. I never let my forecasts influence my longer-term investment portfolio. Rather than trying to be the unicorn that can “beat the market” all the time, I stick to a strategy that I believe puts long-term probabilities in my favor.

You can learn more about my full investment process here.